And like most parents of any age, I feel extraordinarily blessed. In fact, I feel like the luckiest person in the world. I’m enjoying the final weeks of my maternity leave, savoring all those bonding moments with Mina: nursing her, snuggling with her while she sleeps on my chest, and seeing her face light up as she smiles at me and makes the cutest little cooing sounds. I also love watching Davin interact with his little sister. Apart from occasional moments of jealousy, Davin is a loving, protective older brother. He loves to give kisses to his little sister, and when she gets fussy, he will let me know right away, often before the baby monitor does.

I know there are downsides to having kids later in life. I’m going to be in my late sixties by the time Mina graduates from high school, and there’s a greater chance that I may not live long enough to know my grandchildren, compared to younger moms.

But I mostly see upsides to being an older mom. I’m more self-confident and laid back than I was in my 20s or 30s, and I don’t often sweat the small stuff. I have a well-established career and the financial resources to afford a nice home for my family. And I have two very strong incentives – Davin and Mina – to focus on my health, to ensure that I remain healthy enough to live a long life (I plan to live to at least 100) and thrive well into my twilight years.

I’m very lucky that I have a partner who is as passionate as I am about creating a wonderful life for our family. Collin is a trained chef who makes delicious, healthy meals for our family. He enthusiastically tackles DIY home projects (of which there are many in our 130-year-old Victorian house), like coming up with clever storage solutions in the kitchen and organizing our entire basement. He takes great care of the yard, planting lots of beautiful flowers and growing a garden that will yield fresh herbs, fruits and vegetables all summer long. Collin has chosen to be a full-time dad for at least the next few years, putting all of his love and energy into raising our children and taking care of our home. As I said, I’m the luckiest person in the world.

Even as lucky as I am, though, there are still a lot of challenging moments in my motherhood journey. There are many moments when Davin, who struggles with emotional regulation, has epic meltdowns that leave me feeling like I’m at the end of my rope (and not coincidentally, I imagine, those meltdowns often happen at the exact moment when Mina is loudly demanding to be fed). I am navigating the path of learning how to parent a neurodivergent child, like learning about all the resources Davin will need to support his education, and learning how important it will be to aggressively advocate for Davin throughout this journey…to say nothing of learning how to be an effective parent to a child who seldom cooperates or responds in the way I want him to. With all the demands of both of my children, and the demands of, well, life…I often feel like I’m working two full-time jobs. And I haven’t even returned to work yet!

I know we’ll make it work, of course. We made it work when I returned to work five years ago, and we’ll make it work this time. But I’m also under no illusion that life is going to be easy anytime soon…or anytime in the next 18 or so years, for that matter. Collin and I have been going to couple’s therapy for several years now, and if we hadn’t put this deliberate focus on our relationship, I’m not sure we would still be together. Being a parent is stressful, even on the good days. It’s little surprise that the research shows that childless couples are generally happier than those with kids.

But the thing is, I didn’t choose easy. I chose extraordinary. I wholeheartedly chose to be a mom, knowing that my life would most certainly get a lot more challenging, but also recognizing that the best things in life are never easy. I knew that being a mom would bring me meaning and fulfillment in a way that nothing else could.

At the same time, I knew that I didn’t want to be a full-time mom. I am beyond grateful to Collin that he is embracing his role as a full-time dad. It’s wonderful that I don’t have to worry about finding daycare for Mina, or backup care for Davin every time he’s sick or school is closed (which I’m learning happens with ridiculous frequency!). But I know myself well enough to know that my career is also a big part of what brings me meaning and fulfillment. I love my job and I love my family. I choose both.

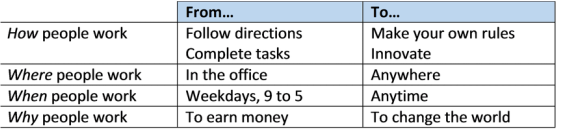

This means, of course, that the elusive, so-called “work-life balance” is always going to be a challenge for me. Thanks to the teachings of Anne-Marie Slaughter and many others, I’ve resigned myself to accepting that I can’t “have it all.” But then, nobody can. We all have to make choices in life, and choosing one thing necessarily means not choosing multitudes of alternatives. For example, I chose to work in HR in the health care industry, in a mid-level leadership role that doesn’t require me to work ridiculous hours. If I hadn’t chosen to be a mom, it’s likely that I would have stayed in consulting or pursued a more senior-level leadership role that required me to work 60+ hour weeks and travel a lot. But that’s not what I want. I love that I can stop working by 5:00 on most days, and then I can shift my focus to having dinner with my family, getting the kids ready for bed, reading bedtime stories, and having time to relax and unwind before I go to sleep.

I recognize that there are real political and societal barriers, especially in the United States, that make it hard for anyone, especially women, to reasonably juggle kids and a career. I will delve more into that topic in a future article. My point here is that I accept that there will always be choices, tradeoffs, compromises to be made…and accepting this is key to my wellbeing. My kids will probably never have the most elaborately-planned birthday parties. I’ll probably never be PTA president. I won’t get to have as many kid-free evenings out as I would like, for many years to come. There will be many days when my kids leave the house with a shirt that’s inside-out or socks that don’t match. And that’s all okay.

I also accept that some days will be really f***ing hard, when it takes every ounce of energy I have just to make it through the day. Those are the days when I will remind myself, over and over again, that I didn’t choose easy. I chose extraordinary. Then I will take a deep breath, and say thank you for all of the blessings in my extraordinary life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed